‘Interstellar’ explores humanity in higher resolution 10 years later

Madison Denis | Contributing Illustrator

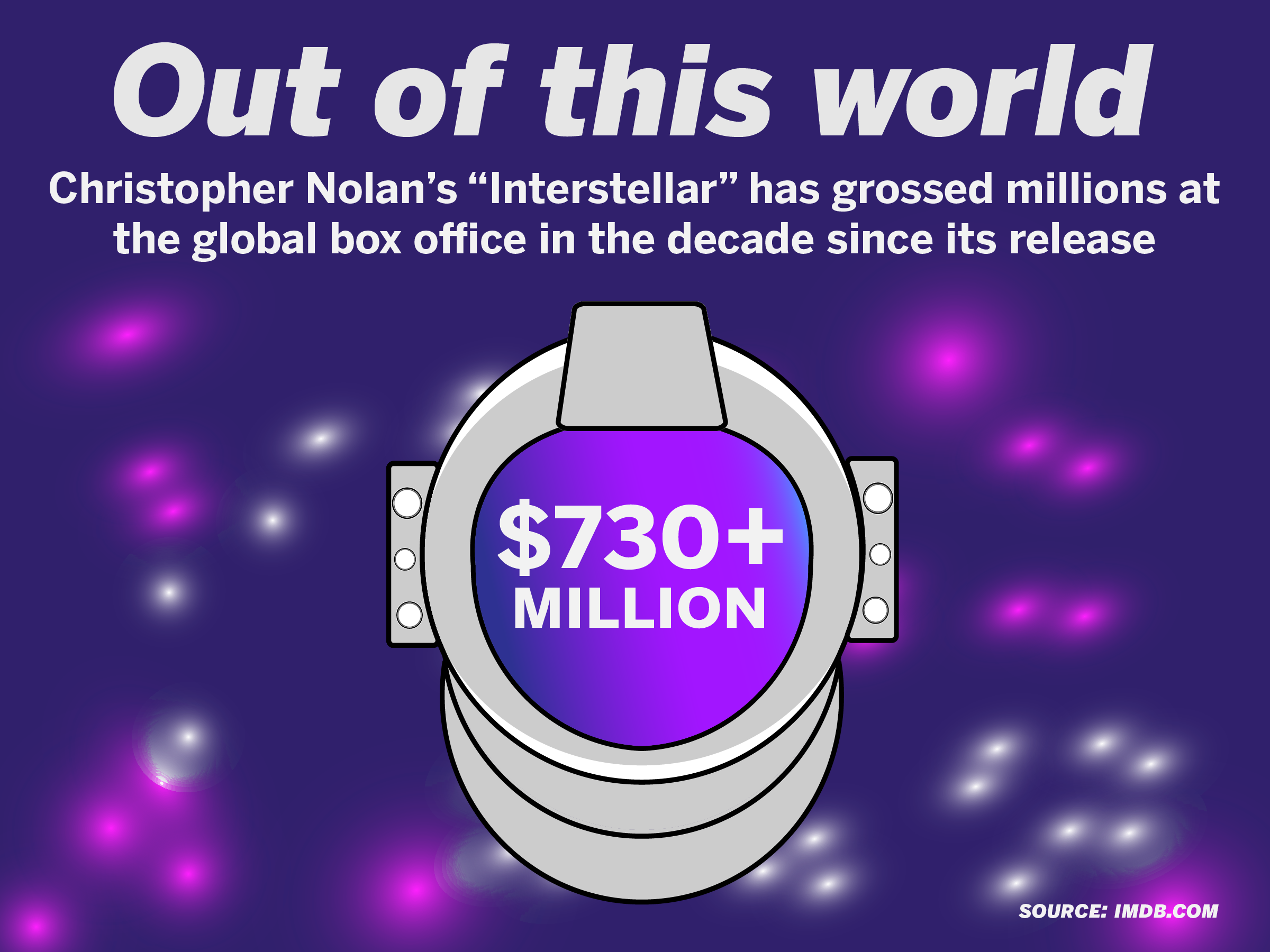

Regal Destiny USA will show Christopher Nolan’s “Interstellar” until Wednesday, celebrating its ten-year anniversary. Presented in IMAX 70mm film, the sci-fi film showcases a father's bittersweet space journey.

Support The Daily Orange this holiday season! The money raised between now and the end of the year will go directly toward aiding our students. Donate today.

When Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) opts to leave his home and his daughter Murph (played at this point by Mackenzie Foy), there’s a clear camera change in Christopher Nolan’s 2014 film “Interstellar.” As Cooper drives away in his truck, we go from seeing events in 35 mm film stock to 70 mm IMAX film stock before a rocket heads into space, never to return to Earth.

There’s an obvious, practical decision for this shift. Nolan presumably figured that Cooper’s odyssey through the reaches of the universe to find a new home for humans deserved to be shown on the biggest screens possible. “Interstellar,” which plays at Regal Destiny USA until Dec. 11, still feels gargantuan on an IMAX screen a decade later.

Above all else, the movie is about a father-daughter relationship. Just as future humans leave Cooper an unconventional opportunity to communicate with Murph, Nolan seemingly uses “Interstellar” to leave behind his own messages about love and science.

As the Los Angeles Times reported at the film’s 2014 release, Nolan’s ninth feature received positive reviews for its spectacle and entertainment. Despite this, the film faced criticism for being “clunky and sentimental at times.”

The combination of hard sci-fi and melodramatic tones, specifically Dr. Brand’s (Anne Hathaway) speech about how love is the ultimate power in the universe, creates a discordant experience. This is especially true since it comes from a director who usually makes serious blockbusters including “Oppenheimer,” “The Dark Knight” and “Memento.”

That sentimentality held me back from enjoying the film the first three times I watched it. But watching it on a big screen, it’s clear that Nolan takes the time and care to examine both sci-fi conventions and humans’ own need for kinship and solace.

When it came to portraying a space odyssey, Nolan didn’t cut corners with his $165 million budget. From planting 500 acres of corn for the ravaged Earth to using visual effects to show what a supermassive black hole might look like, there’s a clear commitment to realism in a genre that can be easily fantastical.

Additionally, Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist Kip Thorne first conceived of the idea for “Interstellar” in 1997 and wrote the treatment for the film. Nolan and his brother Jonathan, the screenwriter, used Thorne’s work as inspiration.

The research pays off. Gargantua, the black hole, and the wormhole that Cooper’s crew uses to travel across the cosmos are shown as spheres and not just two-dimensional circles. There have been plenty of sci-fi blockbusters, like those of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but there’s little exploration of the mysteries of the galaxy and less attention to detail.

Lily Zuckerman | Design Editor

The true magic in “Interstellar” happens when Nolan makes scientific accuracy melancholic. Look no further than when Cooper and Dr. Brand return from a planet with Mount Everest-like waves. Since the gravity on the planet is so strong, Einstein’s theory of relativity forms a situation where one hour on the planet for Cooper and Dr. Brand equals 23 years for everyone back at home. Once the two return to the ship, they find video messages that their loved ones, who think Cooper and Brand are dead, left behind.

The scene is by far the most heartbreaking in the film and points toward more distressing undertones. Cooper sees his kids Murph (now played by Jessica Chastain) and Tom (Timothee Chalamet, Casey Affleck) grow older than him. Nolan doesn’t shy away from how the universe will hurt the humans trying to understand it, as they’re subject to the laws of physics.

“Interstellar” suggests that humans are not wired for the indifference and loneliness that lies out in the void. Wide shots of space that make Cooper’s ship look puny evoke Carl Sagan’s description of Earth as a “pale blue dot.” Hans Zimmer’s score, which at times sounds epic, takes on somber and sometimes horrifying turns.

In typical Nolan fashion, characters mirror each other and represent a spectrum of views on science and humanity. One side is a commitment to progress through science, no matter the cost. Professor Brand (Michael Caine) and Dr. Mann (Matt Damon) represent this camp. On the other end, Tom and Murph’s elementary school teachers reject progress by staying committed to humans currently on earth.

Nolan seemingly finds a healthy balance with Cooper and Murph – and Dr. Brand to a lesser extent – emphasized by an ending that becomes more fiction than science. The final 30 minutes of the movie have received criticism, with comparisons to director M. Night Shyamalan’s endings (as if that’s a bad thing). Once Cooper throws himself into a tesseract built by future humans inside Gargantua, he uses gravity to communicate with Murph through a watch and dust particles in her childhood bedroom, leading to humanity’s survival.

Admittedly, it still sounds a tad absurd a decade later. But it symbolizes an acknowledgment from Nolan, who mostly adheres to science and practical effects in his films, that you need to embrace the irrational to connect with your humanity. Too much rationality or irrationality will lead to distinct but disastrous consequences.

Love may not actually be quantifiable and sentimentality may be foolish. But what’s undeniable is that Nolan’s “Interstellar” is his most reflexive and humanist film, showing love’s powerful pull. We can’t understand all the mysteries of the universe, and our survival as a species on Earth will end at some point. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive for more while still holding on to what makes us human.

Just as in “Tenet,” another misunderstood hit from Nolan, knowing the horrifying consequences of the future doesn’t mean we should do nothing. As Professor Brand’s recitation of the Dylan Thomas poem goes, humans “should not go gentle into that good night / Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Published on December 9, 2024 at 12:50 am

Contact Henry: henrywobrien1123@gmail.com